Main types of attacks 🔗

Updated August 3, 2025

Social engineering 🔗

Social engineering is a manipulation technique used by attackers to trick people into revealing sensitive information, granting access, or performing actions that compromise security. Unlike technical hacking, social engineering targets human psychology—using tactics like urgency, fear, curiosity, or authority to lower defenses. Common examples include phishing emails, fake tech support calls, and impersonation attempts.

These attacks often appear legitimate, making them hard to detect. An attacker might pose as a coworker, vendor, or IT staff to request login credentials, access to systems, or confidential data. Even a small mistake—like clicking a malicious link or sharing internal details—can lead to a larger breach.

Awareness is the best defense. Always verify unexpected requests, especially those asking for sensitive information or urgent action. If something feels off, report it to your IT or security team immediately—better safe than sorry.

Video of a Social Engineering Attack Demonstration

This video demonstrates how easily scammers can gather personal information and gain unauthorized access to someone’s cell phone account using details found on social media. This demonstration was conducted with the participant’s full consent to illustrate common social engineering tactics and highlight the importance of protecting your personal information online.

Source: Instagram

Examples

- Text messages claiming your account has been disabled and asking you to enter your password—often through a fake login page.

- Phone calls requesting personal information or threatening legal action, arrest, or account closure if you don’t comply.

- Abuse of the “Forgot Password” feature on breached websites to gain unauthorized access.

- Social media posts or quizzes designed to collect personal details like your pet’s name, favorite car, or childhood street—often used to guess security questions.

Intelligence gathering (Open-Source Intelligence [OSINT] ) 🔗

Not a form of attack but rather a set of information-gathering techniques that can support various types of attacks—especially social engineering. The more personal details an attacker collects on their potential victims, the more convincing and targeted their attacks can become.

It is the process of collecting publicly available information from sources like social media, websites, and public records. Attackers use OSINT to gather personal details—such as maiden names, pet names, or birthdays—that help them bypass security questions or craft targeted attacks. Because this information is often shared openly, it highlights the importance of careful privacy settings and cautious online sharing.

Examples

1. Password Guessing from Public Info

An attacker targeted a small business owner by collecting their personal details online.

- Date of birth from birthday wishes on Facebook.

- Pet names from Instagram posts.

- Favorite sports team from Twitter.

Used personal info to guess security questions and passwords.

Gained access to email, which allowed for password resets on banking and e-commerce platforms.

2. Pretexting for Voice Phishing (Vishing)

Attackers called customer service pretending to be a bank customer.

Full name, address, phone number, and partial credit card info—all scraped from breached databases and social media.

Used confident pretexting (e.g., “I just moved, can you help me reset my online banking access?”).

Tricked support staff into resetting the real account’s login, locking out the real customer.

3. Targeting Developers via GitHub

Attackers browsed public GitHub repositories to find credentials accidentally left in code (API keys, passwords).

GitHub search, email addresses, usernames matching LinkedIn profiles.

Used these credentials to access cloud environments or databases.

In one case, a company’s internal customer data was stolen and sold on the dark web.

4. Spear Phishing via LinkedIn Information

Attackers identified employees of a financial firm via LinkedIn, noting who worked in finance and IT.

Job roles, email patterns, office locations, manager names.

Crafted emails impersonating senior leadership with fake invoice requests or requests for password resets.

Multiple employees clicked malicious links, leading to credential theft and unauthorized access to internal systems.

5. Possible intelligence gathering examples on social media

Phishing / whaling 🔗

Phishing is a cyberattack where attackers send fraudulent emails or messages (via Messenger, Instagram, Whatsapp, etc.) designed to trick people into revealing sensitive information—like passwords or credit card numbers—or clicking malicious links. These messages often appear to come from trusted sources, making them deceptive and effective at stealing data or installing malware.

Whaling is a targeted form of phishing aimed specifically at high-profile individuals such as executives or senior managers. Because these “big fish” have access to valuable information and critical systems, whaling attacks are often more sophisticated and personalized, using detailed research to increase their chances of success.

See also: Phishing with AI-Generated Content

Examples

What might they be trying to acquire with these methods?

- Steal sensitive data like credit card and login information.

- Install malware on a victim’s machine.

- Request money or plane tickets.

New methods of spoofing

- You might receive a calendar invite from a spam accounts that contains dangerous links. You might have received or downloaded them from suspicious links or ads.

- You may receive these kind of messages from hacked accounts: “Hey! How have you been doing?”, “I can’t believe you are in this video!”, “is this you?” accompanied almost every time by a link as they are trying to use shame or fear to make you click on it by impersonating someone you know to gain your trust.

Increase in phishing attacks…

Between 2024 to 2025 there’s been an increase of 156% in phishing attacks, and now compose the majority of cybersecurity investigations by expert. It is also the most costly type of attack for businesses.

Phishing-as-a-service(1) platforms such as Tycoon 2FA are democratizing these kinds of attacks thanks to their sophisticated capabilities and relatively low cost. For just $200-300 per month, these toolkits offer convincing pre-made phishing pages for the major workplace platforms, such as Microsoft 365 and Google Workspace, as well as functions to steal session cookies(2) and bypass 2FA/MFA(3).

The security industry’s move toward pushing passkeys(4) as the primary, new mainstream form of account authentication comes against this backdrop of rising email compromises. Passkeys are being tipped as a phishing-resistant form of account authentication.

-

A type of cybercrime where criminals sell ready-made phishing tools and services to others, making it easy for anyone — even without technical skills — to launch phishing attacks.

-

A session token (also called session cookie) is a unique, temporary identifier that a server assigns to a user after they log in. It keeps the user authenticated as they navigate a website or app without needing to log in again on every page.

-

A way to make your accounts more secure by requiring two or more proofs of identity.

See Glossary > MFA (Multi-Factor Authentication) — 2FA (Two-Factor Authentication).

-

Passkeys are a new, safer way to sign in to apps and websites without using passwords. Instead of typing a password, you use your device (like your phone or computer) to confirm it’s really you — with a fingerprint, face scan, or PIN. Passkeys are harder to steal and protect you better from phishing and hacking.

Phishing-as-a-Service 🔗

Modern phishing attacks have evolved to circumvent even sophisticated security measures like multi-factor authentication (MFA). One emerging threat involves attackers using phishing-as-a-service platforms that simplify the process of stealing user credentials. These platforms allow attackers to quickly set up fake login portals for popular services, including email and cloud storage providers, and capture sensitive information with minimal technical expertise.

Unlike traditional phishing, which relies on tricking users into revealing passwords, these advanced services can bypass MFA protections by intercepting authentication tokens in real time. When a user attempts to log in to a compromised portal, the attacker simultaneously uses the captured credentials to access the legitimate service, completing the MFA challenge without alerting the victim.

This approach significantly increases the risk of account compromise, as attackers gain access to accounts even when additional layers of security are enabled. Awareness and training are crucial in mitigating these risks, emphasizing careful scrutiny of login prompts, unusual login requests, and the use of secure authentication methods that are resistant to token interception.

Organizations are encouraged to combine user education with technical controls such as hardware-based security keys, anomaly detection, and monitoring for unusual login activity to reduce exposure to these sophisticated phishing campaigns.

Source: HackRead.com — New VoidProxy Phishing Service Bypasses MFA on Microsoft and Google Accounts.

Spoofing 🔗

Email Spoofing involves forging the sender’s email address to make a message appear as if it came from a trusted source. Attackers manipulate email headers—specifically the “From” field—so the recipient is more likely to open the message or act on its contents. While the email may look legitimate, the actual sending server or reply address often reveals it’s fraudulent.

Website Spoofing is when attackers create fake websites that closely mimic legitimate ones, such as login pages for banks or services. The goal is to trick users into entering their credentials, which are then captured and used maliciously. These spoofed sites often have nearly identical designs and use misleading URLs to deceive victims.

Domain Spoofing refers to the use of lookalike domain names, such as replacing letters with similar characters (e.g., g00gle.com instead of google.com), to impersonate legitimate organizations. This technique is commonly used in phishing campaigns and malicious ads to lure users into thinking they’re visiting a trusted site when they’re not.

Examples

1. Email spoofing

-

Fake CEO Request

The email looks like it’s from the CEO, but the actual sending server isn’t authorized by your company.From: [email protected] To: [email protected] Subject: “Urgent Wire Transfer” Body: “Please wire $25,000 to the vendor account below by end of day.” -

Spoofed IT Helpdesk

The link leads to a fake login page designed to steal credentials.From: [email protected] Subject: “Password Reset Required” Body: “We detected unusual activity. Click here to reset your password.” -

Internal Phishing Attempt

The attachment contains malware, and the header was forged to look internal.From: [email protected] Subject: “Updated Benefits Form” Body: “Please download and review the attached form.”

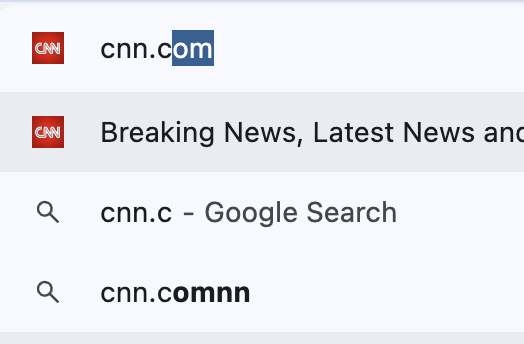

2. Domain/website spoofing

- Domain names can include non-roman characters, like

www.りんご.com(means ringo, or apple in Japanese). - That means that

www.apple.còm(see theòcharacter instead of ao) is a possible domain for a website. - Similarly,

www.аpple.com(where theais a Cyrillic character, not the assumed Roman letter) looks nearly identical to the real site. This kind of domain spoofing is highly deceptive, making it almost impossible for users to realize they’ve landed on a fake website. Adding the domain name/website address in 1Password will help counter these spoofing attempts by not presenting your login credentials as there is a mismatch.

Domain spoofing example

cnn.comnn.

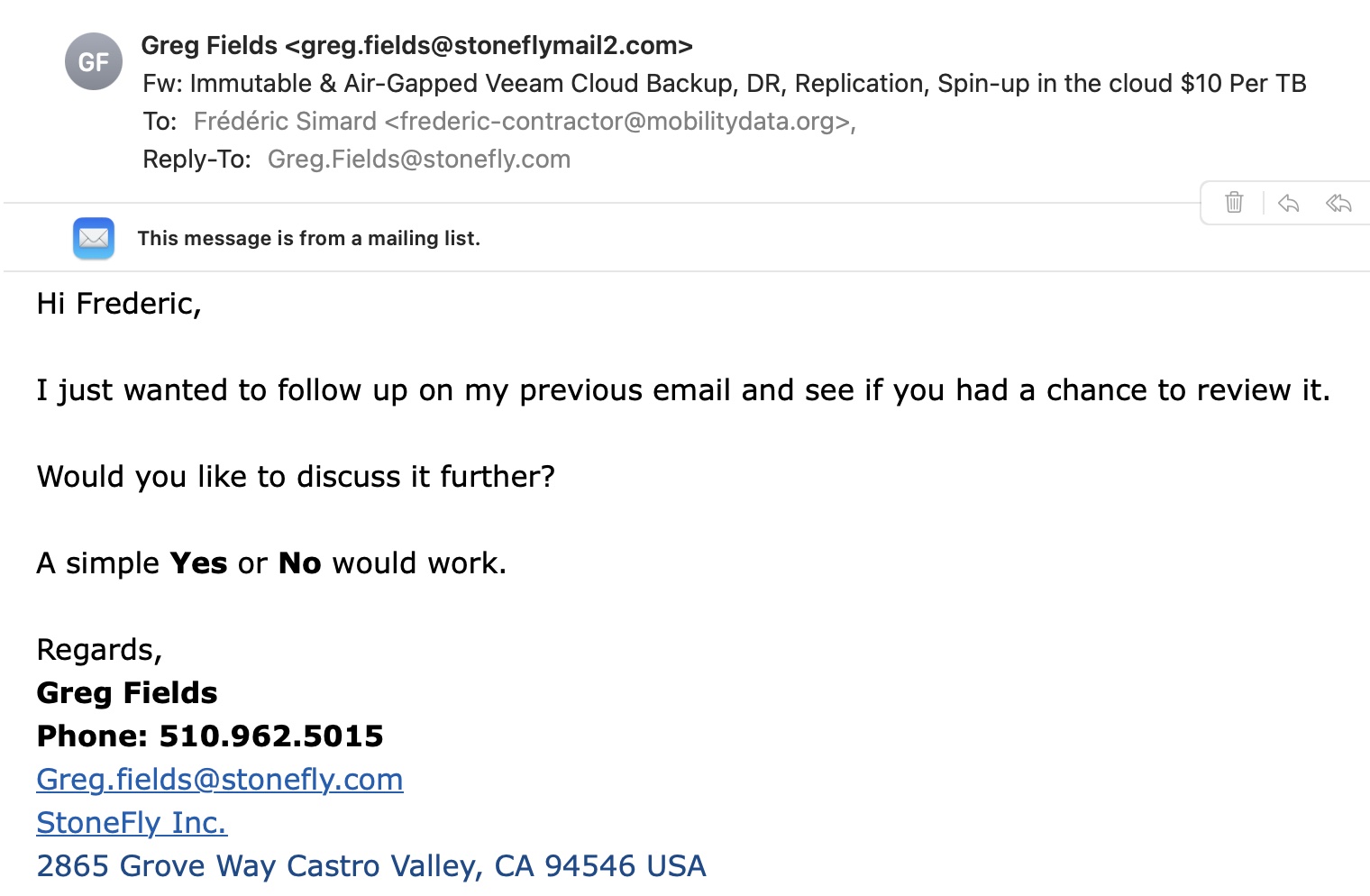

Screenshots of real spoofing attempts

1. Attempt at impersonating Eric

2. Paypal scam

Supply Chain Attack 🔗

A supply chain attack targets less secure elements in an organization’s supply or service network—such as third-party vendors, software providers, or hardware manufacturers—in order to compromise the end target. Instead of attacking a company directly, attackers breach a trusted partner or product and use that access as a backdoor.

These attacks are dangerous because they exploit trust. Once a compromised component is integrated, it can silently spread malware or provide access deep into systems that would otherwise be well protected.

Always vet vendors, monitor updates, and validate the integrity of third-party software and services.

Examples

- XcodeGhost (2015): A modified version of Apple’s Xcode development tool was distributed on unofficial sites in China. Developers unknowingly used this tainted Xcode to build apps, which were then uploaded to the App Store. The apps contained hidden malware capable of collecting user data and sending it to remote servers.

- Homebrew GitHub Token Leak (2020): Homebrew, the popular macOS package manager, had a security incident where an attacker gained access to its GitHub repositories via a compromised developer credential. Although no malicious code was inserted, the incident highlighted the risk of tampering with widely trusted developer tools.

- Targeted Attacks via Pirated Software: Attackers have bundled malware into pirated versions of macOS software (like Adobe or productivity tools). These cracked apps are distributed outside the App Store, often via torrent sites, and can contain backdoors, crypto miners, or spyware.

- PyPi/NPM Packages Used in macOS Development: macOS developers relying on third-party libraries from PyPi or NPM have been exposed to typosquatting attacks—where malicious packages with names similar to popular ones are installed and executed during build or runtime, potentially compromising the system.

- SolarWinds (2020): Attackers inserted malicious code into a trusted software update, affecting thousands of organizations, including U.S. government agencies. macOS users of SolarWinds products were also affected, specifically those using the Orion platform and potentially other products where the compromised updates were distributed.

- CCleaner (2017): Hackers compromised the popular PC optimization tool to install backdoors on millions of systems via a legitimate software update.

Reminder

Always use official sources for developer tools, avoid pirated software, and verify the integrity of any third-party package or dependency.

Viruses & Malwares 🔗

Viruses and malwares are malicious programs designed to damage, disrupt, or gain unauthorized access to systems and data. They can spread through email attachments, downloads, infected websites, or USB devices. Once inside a system, malware can steal information, encrypt files (ransomware), or allow attackers remote access. Staying cautious online and keeping software up to date are key defenses.

Macs and iPhones are not safe from these attacks

Contrary to popular belief, Mac and iPhones are—despite being very secure platforms—regularly targeted by people with bad intentions.

A prime example is Pegasus, a highly sophisticated spyware developed by NSO Group. In August 2016, Pegasus exploited three previously unknown vulnerabilities (two on iPhones and one on Macs) allowing attackers full access to calls, messages, camera, mic, and more, without any user interaction.

Apple was alerted immediately and released patches 10 days later, which is remarkably fast—but it still meant users were vulnerable during that window. Similarly, in September 2021, Pegasus leveraged a “zero-click” (1) BlindPass exploit in iMessage and Mac CoreGraphics. Apple patched it in just one week, but again emphasized that even the most secure devices can be compromised before a fix is released.

-

A “zero-click” event, in the context of cybersecurity, refers to a cyberattack that requires no interaction from the victim.

Malicious SVG files 🔗

SVG files are text-based images and can contain JavaScript, links, or other code. Attackers hide harmful scripts or tracking inside an SVG sent as an email attachment or embedded on a web page. When a user or an AI tool opens or renders that SVG, the embedded code can run: it might steal data, call back to an attacker-controlled server, exploit a browser or viewer bug, or trigger unwanted downloads. Because the file looks like a harmless picture, it’s easy to miss.

Treat incoming SVGs like executable content. Block or quarantine SVG attachments, or automatically convert them to safe raster formats (PNG/JPEG) before preview. Ensure viewers and web apps sanitize SVGs (strip scripts, external references, and dangerous attributes), apply strict Content Security Policies, keep rendering libraries up to date, and scan attachments with malware detection. Finally, educate users not to open or upload unexpected SVGs and restrict which services and AIs can render files from untrusted sources.

Examples

- Email Attachments: Opening malicious files disguised as invoices, resumes, or reports.

- Phishing Links: Clicking fake links in emails or messages that lead to infected websites.

- Infected Downloads: Installing software or files from untrusted sources (e.g., pirated apps or cracked tools).

- USB Drives: Plugging in compromised USBs, which can auto-run malware.

- Malicious Ads (Malvertising): Clicking on ads on compromised or fake websites.

- Fake App Updates: Downloading what appears to be a system or software update from a non-official source.

- Mobile Apps: Installing apps from outside the official app stores, especially on jailbroken/rooted devices.

- Drive-by Downloads: Simply visiting a compromised website can trigger an automatic, invisible download.

Articles

- “Hackers are using Google.com to deliver malware by bypassing antivirus software. Here’s how to stay safe” - The use of Google’s domain is central to the deception: because the script loads from a trusted source, most content security policies (CSPs) and DNS filters allow it through without question.

Ransomware 🔗

Important

Paying the attackers is not a recommended solution. It encourages further attacks—often sooner and with higher demands—since they now see you as an easy target who likely hasn’t yet fixed the original vulnerabilities that allowed them to ransom you the first time.

See Security > Ransomware attack on what to do if it happens to you.

Ransomware is a type of malicious software that encrypts files or locks access to a system until a ransom is paid—often in cryptocurrency. Victims are usually given a deadline and threatened with permanent data loss or public exposure. Ransomware attacks can target individuals, businesses, hospitals, and even governments, causing severe disruption and financial loss.

Attacks of this type have vastly increased since COVID due to the easy deployment (thanks to kits you can buy on the dark web) and high-reward. The attackers can also resell information like credit cards, social security numbers etc, especially when packaging multiple victims’ information to be sold in bulk, becoming even more valuable.

See Emergencies > Ransomware attack > Decryptors, tools and solutions for resources regarding the possible decryption of files from known attacks.

Examples

- Phishing Emails: Opening attachments or clicking links in fake emails (e.g., “invoice” or “package delivery”).

- Malicious Downloads: Installing cracked software, games, or tools from untrusted websites.

- Infected Websites: Visiting compromised websites that trigger drive-by downloads.

- Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) Attacks: Hackers gain access through weak or exposed remote desktop credentials and passwords.

- USB Devices: Using infected external drives or devices with autorun malware.

- Software Vulnerabilities: Exploiting outdated or unpatched systems to silently install ransomware.

Articles

- “Anubis ransomware adds wiper to destroy files beyond recovery” - The Anubis ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) operation has added to its file-encryptimg malware a wiper module that destroys targeted files, making recovery impossible even if the ransom is paid.

- “North Korea targeting Indian crypto job applicants with malware” - The campaign observed by Cisco Talos reflects other efforts by North Korea to infect job seekers with malware in an effort to get information on the attributes of successful applicants in the crypto space — potentially useful data for North Korea in order to get their citizens hired.

The Surge of Ransomware Attacks Since the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic fundamentally transformed the cybersecurity landscape, creating unprecedented opportunities for cybercriminals to exploit vulnerabilities. Since the start of the pandemic, ransomware attacks have increased by nearly 500 percent, with the average ransom payment climbing 43 percent from the last quarter of 2020 to an average of over US$200,000. This dramatic escalation was fueled by the rapid shift to remote work, which expanded attack surfaces and left many organizations scrambling to secure hastily implemented digital infrastructures.

The scale of this cyber threat became evident through various statistical reports. There was an obvious and extreme rise in cyberattacks involving ransomware creating a global surge of ransomware attacks by 102 percent between May 2020 and May 2021. According to a report by Skybox Security, the creation of new ransomware samples increased by 72 percent during the first half of 2020, with 77 ransomware campaigns being observed during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic. This surge wasn’t limited to frequency alone - the sophistication and scale of attacks also intensified significantly.

The impact extended across all sectors, with cybercriminals specifically targeting vulnerable organizations during a time of global crisis. Between May 2020 and May 2021, the FBI saw complaints about cyber crime jump by 1 million. Healthcare systems, educational institutions, and businesses transitioning to remote work became prime targets. The most common type of malware is ransomware, use of which increased by 36 percent in Q2 2020. This trend highlighted how cybercriminals opportunistically exploited the pandemic’s disruption to maximize their criminal activities.

The pandemic’s legacy in cybersecurity continues to shape threat landscapes today, as organizations must now contend with permanently elevated risk levels and more sophisticated attack methods that emerged during this period of global vulnerability.

Sources

The Ransomware Economy

How Ransomware Syndicates Operate

graph TD

classDef white fill:#ffffff,stroke:#000000,stroke-width:1px;

classDef dark fill:#3859FA,stroke:#000000,stroke-width:0px;

classDef light fill:#96A1FF,stroke:#000000,stroke-width:0px;

classDef joint fill:#FFFFFF,stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px;

1("<span style='color: white;'>Developers</span>") --- X((" "));

2("<span style='color: white;'>Packer Developers</span>") --- X;

X --- Y;

Y --> A;

3("<span style='color: white;'>Analysts</span>") ---- Y((" "));

4("<span style='color: white;'>Access Sellers</span>") ---- Y;

5("<span style='color: white;'>Botmasters</span>") ---- Y;

A("<span style='color: white;'>_**Threat actors**_

—

Operators

↓

Sell RaaS

↓

Affiliates</span>") --> B("<span style='color: white;'>Laudering services</span>") --> C("<span style='color: white;'>Cryptocurrency Exchanges</span>");

A -.-> D("<span style='color: white;'>Negotiating Agents</span>");

A --- Z((" ")) --> R1{{Ransomware Brokers}};

A --> R2{{Victims}};

R2 --> R3{{Legal Counsel}} --> R1;

R3 --> R4{{Insurance Providers}};

R2 --> R5{{Incident Response Firms}};

D -.- |Negotiation & Payment|Z;

class 1,2,3,4,5,A,B,C,D dark

class R1,R2,R3,R4,R5 light

class X,Y,Z joint

linkStyle 0 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 1 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 2 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 3 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 4 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 5 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 6 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 7 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 8 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 9 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 10 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 11 stroke:#96A1FF,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 12 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 13 stroke:#96A1FF,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 14 stroke:#96A1FF,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 15 stroke:#96A1FF,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 16 stroke:#96A1FF,stroke-width:2px

linkStyle 17 stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2pxflowchart LR

classDef white fill:#ffffff,stroke:#000000,stroke-width:0px;

classDef dark fill:#3859FA,stroke:#000000,stroke-width:0px;

classDef light fill:#96A1FF,stroke:#000000,stroke-width:0px;

classDef joint fill:#FFFFFF,stroke:#3859FA,stroke-width:2px;

A(LEGEND:) ~~~ T

T("<span style='color: white;'>Dark Web Service Providers</span>") ~~~ X

X{{"Victim-side Service Providers"}}

class A white

class T dark

class X lightDark Web Service Providers

Developers

Write the ransomware software and sell it to threat actors for a cut of the ransom.

Analysts

Evaluate the victim’s financial health to advise on ransom amounts that they’re most likely to pay.

Access Sellers

Take advantage of publicly disclosed vulnerabilities to infect servers before the vulnerabilities are remedied, then advertise and sell that access to threat actors.

Botmasters

Create networks of infected computers and sell access to those compromised devices to threat actors.

Negotiating Agents

Handle interactions with victims.

Laundering Services

Exchange cryptocurrency for fiat currency on exchanges or otherwise transform ransom payments into usable assets.

Operators

The entity that actually carries out the attack with access purchased from botmasters or access sellers and software purchased from developers or developed in-house. May employ a full staff, including customer service, IT support, marketing, etc. depending on how sophisticated the syndicate is.

Affiliates

Purchase ransomware as a service from operators & developers who get a cut of the ransom.

RaaS

Victim-side Service Providers

Ransomware Brokers

Brought in to negotiate and handle payment on behalf of the victim and act as intermediaries between the victim and operators.

Legal Counsel

Often manage the relationship between the broker, insurance provider, and victim, and advise on ransom payment decision-making.

Incident Response Firms

Consultants who assist victims in response and recovery

Insurance Providers

Cover victim’s damages in the event of an attack.

Man-in-the-middle attack 🔗

A Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attack occurs when a malicious actor secretly intercepts and possibly alters communication between two parties—often without either side knowing. The attacker positions themselves between the user and a legitimate service (like a website or app), allowing them to steal data, insert malicious content, or impersonate one of the parties.

Always use secure, password-protected Wi-Fi, check for HTTPS in website URLs, and avoid accessing sensitive accounts on public networks.

Examples

- Public Wi-Fi Eavesdropping: On unsecured Wi-Fi networks (like in cafés or airports), attackers can intercept login credentials, messages, or banking details. Using a VPN adds an extra layer of security that protects you from such attacks.

- Fake Wi-Fi Hotspots: Hackers set up a network with a name like “Free_Coffee_Shop_WiFi” to lure users and capture their data. Again, use a VPN when accessing a Wifi network that you are not familiar with.

- DNS(2) Spoofing: Redirecting users from a legitimate website to a fake one that looks the same, tricking them into entering sensitive information.

- HTTPS Stripping: Downgrading secure connections to unencrypted ones, allowing attackers to read or modify traffic.

- Session Hijacking: Stealing a user’s session token(1) to impersonate them without needing credentials.

-

A session token (also called session cookie) is a unique, temporary identifier that a server assigns to a user after they log in. It keeps the user authenticated as they navigate a website or app without needing to log in again on every page.

-

The Internet’s system for converting alphabetic names into numeric IP addresses. For example, when a Web address (URL) is typed into a browser, DNS servers return the IP address of the Web server associated with that name.

AI-powered attacks 🔗

Hidden Instructions in Emails 🔗

A new attack method hides secret instructions inside normal-looking emails. When AI assistants (like chatbots) read the message, they can be tricked into showing fake warnings such as “Your account is in danger” or “Call this number for help.” These messages look legitimate but are designed to mislead. The phone numbers and links lead directly to scammers, not real support. Because the AI doesn’t realize it’s being manipulated, users are unknowingly guided toward fraud.

Prompt Injection 🔗

Prompt injection is when attackers hide malicious instructions inside text, documents, or even websites. If an AI assistant processes this hidden text, it may ignore its original instructions and instead follow the attacker’s commands.

This could mean leaking sensitive information, generating harmful outputs, or redirecting users to unsafe websites. Prompt injection is especially dangerous because it hides inside content that looks harmless at first glance.

Phishing with AI-Generated Content 🔗

Traditional phishing emails try to trick users into giving away passwords or clicking malicious links. With AI, attackers can now create emails that look much more professional, free of spelling mistakes, and even personalized.

These messages can seem to come from a trusted source, making them harder to spot. The end goal is still the same: steal sensitive information or install malware.

Data Poisoning 🔗

In some cases, attackers target the AI system itself. They insert false or harmful data into the information sources that the AI relies on (like forums, public documents, or knowledge bases).

Later, when the AI gives advice, it unknowingly repeats this poisoned data. This can spread misinformation, weaken trust in the system, or even cause users to make unsafe choices based on the manipulated output.

Malicious Connectors 🔗

Platforms like ChatGPT often connect to services like Google Drive through connectors so they can read files and help users. Attackers have found a way to abuse these connectors by tricking an ChatGPT into accessing a linked Drive account or by compromising the connector itself — to copy or share sensitive files without the owner’s intent. That might look like an AI responding with private file contents, generating links to download documents, or forwarding files to attacker-controlled locations. Because the connector already has access, the AI can inadvertently become the path that moves data out.

Use this as a reminder: treat connectors like keys. Limit which apps have Drive access, review connector permissions regularly, and require strong authentication and explicit confirmation before any AI or connector shares files outside your organization.